I encountered an interesting problem while assembling a couch a while back. It led me to think more about tools, assembly, building, design, and how they can all influence each other.

While unpacking the components, I had set myself up for an assembly task: reading instructions first, organizing and labelling the hardware, and giving myself both a clear space and clear schedule to accomplish the task. (More to explore: Assemble, Build, Design) I set out, equipped with my tools: A hex allen key, a screwdriver, and sense of determination.

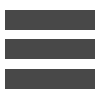

During assembly, I found myself stuck at a particular step. To connect piece A to piece B, they had to be level with each other. However, when resting horizontally, they would only be level when bolted. (More to explore: How to navigate chicken and egg problems)

On the box was an icon of two silhouettes, indicating the job was for two people. I presume that the intent was for one person was to hold the pieces level, and the other to apply the bolts. I was missing a necessary tool!

- Someone to hold piece A level to B while bolting

(Of course, people aren't tools. But the instructions suggested otherwise!)

I hadn't yet known anyone to call on to help, so I had to rely on another tool, my sense of determination. My initial reaction was to look for a substitute. Something that can raise piece A to meet piece B. A block could work, but it would have to be aligned perfectly to meet the bolts. A carjack would be better, but I didn't have one. (More to explore: Building the tools you need)

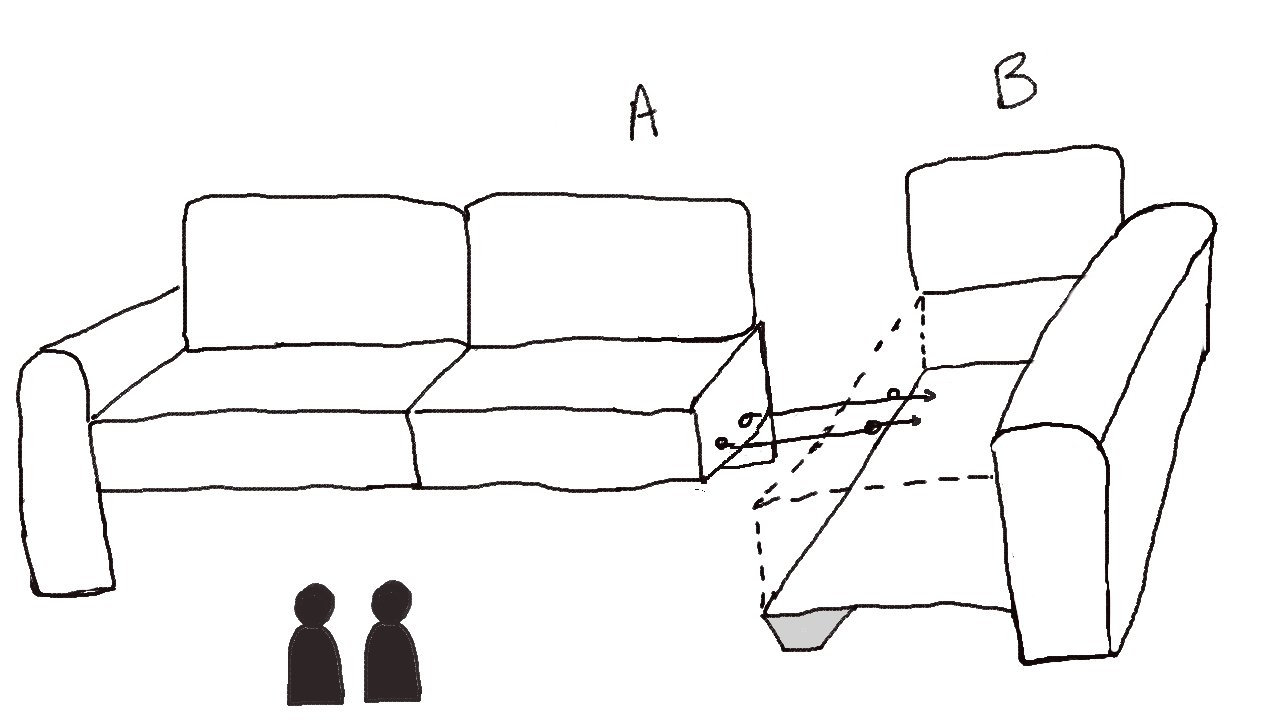

Instead, we turn the problem around, literally! Instead of looking for tools to fight gravity, we can use gravity as tool to help us. By turning the couch (safely) onto its side, piece A would fall onto piece B, and can be pivoted around to line up with the bolts. An additional step of removing the arm of piece B beforehand allowed to it rest level while positioned vertically. This required taking a step back, re-evaluating the tools we had, and re-applying them. This is an example of leaving the assembling mindset, into the building mindset.

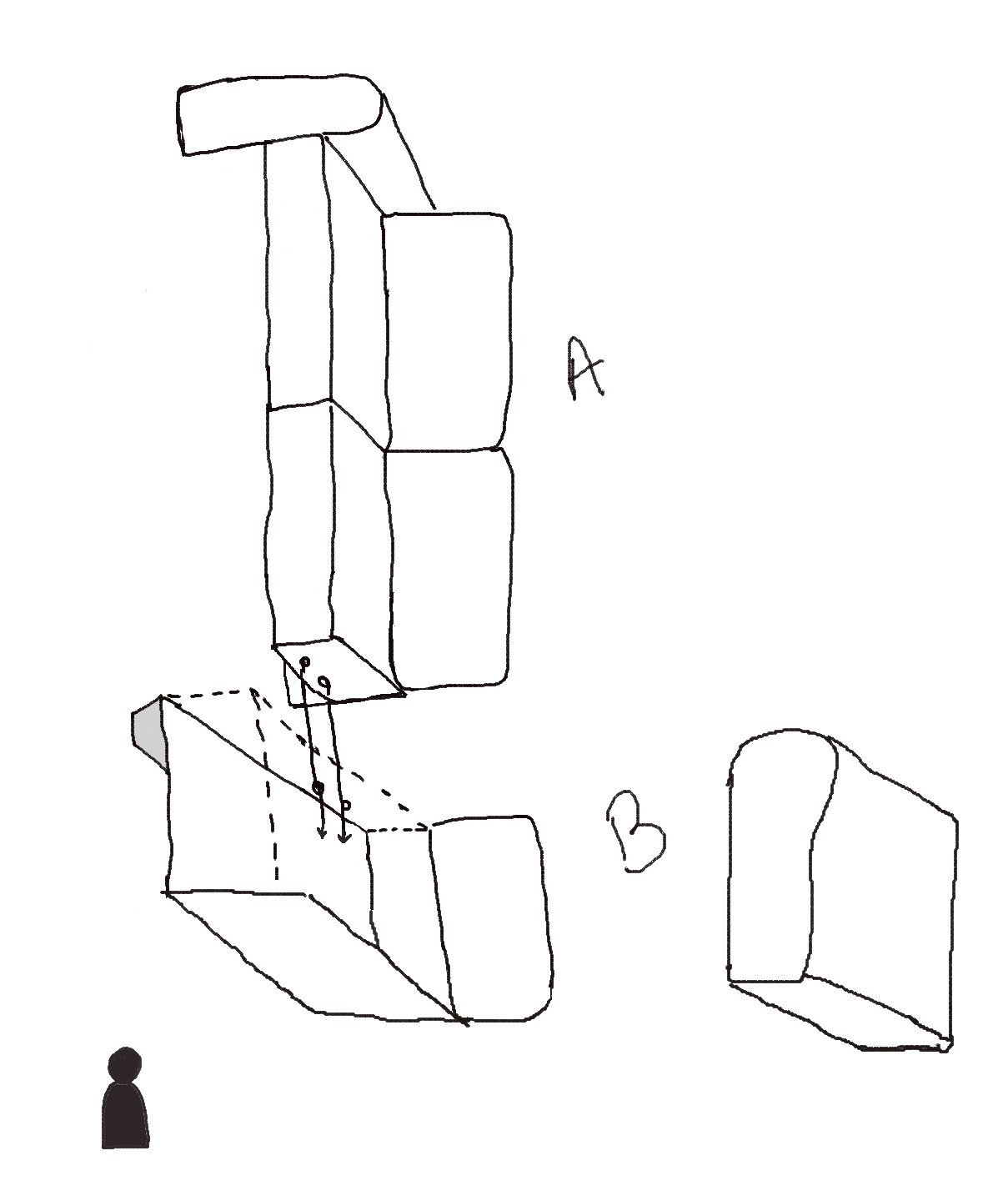

While we are leaving the assembly mindset, there is an opportunity to speak to the design of the couch, too. Consider putting feet on piece A so that it rests level with piece B while resting horizontally, even without being bolted. Then the assembly task would be much easier (both for one and two people). Furthermore, if piece A and piece B could sit level by themselves, they could also be modularized into separate furniture pieces as well. Sometimes, a good design can eliminate the need for a tool entirely.

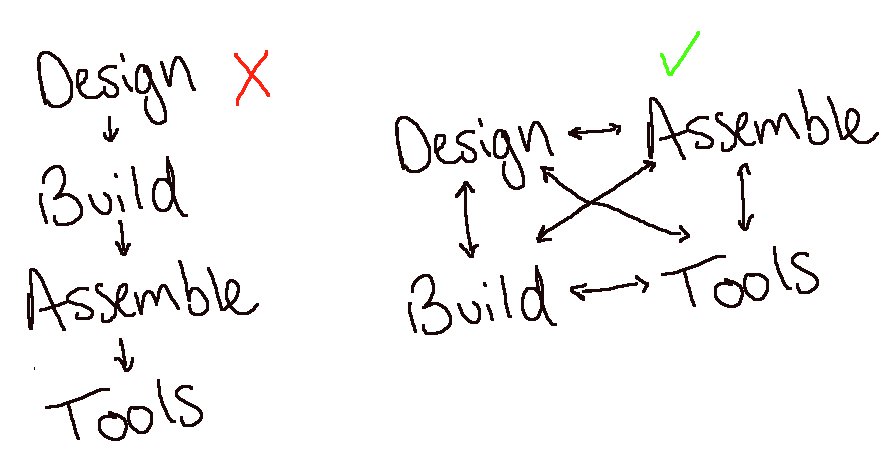

The couch is a metaphor for our creation process in general. We might be tempted to think of creation as a top down process, where design dictates building, building dictates assembly, and assembly dictates the tools we need. You may be a victim of this mentality if you believe that the more valuable thoughts are the ones encountered in design, and there is nothing to be learned in a mundane task like assembling furniture.

If we take this cascading approach, the problems will cascade, too. Similarly, the tools we available shouldn't solely dictate our designs, but that happens as well (Think of all the unnecessary chatbots that have been added to websites lately.) The couch example shows that by touching on one, the rest are all affected. Each element influences, but does not decide, the others.

While teaching in a postgraduate program, the first semester was a matter of assembly. The task was to show students what the tools are (databases, servers, browsers, document object model), and how they can be used to accomplish a fixed goal. This fixed goal was decided for them, such as a content management system for a simple blog or school database.

In the second semester, we encourage more freedom in the building process, and show how adjustments in the tools or frameworks available adjust assembly as well. This is more obvious while iterating on project plans, wireframes, database designs, and minimum viable products (MVPs). The more you plan, the better your builds are, the more you build, the better your plans are.

In the third semester and beyond, students use their newly gained experience of assembly and building to further influence the designs of their projects. That, in turn, will influence them to seek new tools and building processes in a cycle. The teaching process is kind of like starting an engine for a few cycles, and then letting it run on its own.

I have found similar motivations while exploring the Micromasters for Statistics and Data Science. We learn the tools (classifiers, neural networks, visualizations, clustering, optimization, probability) that help us solve preset problems and exercises. The learning doesn't end by collecting every tool, or by fixating on which circumstances exactly match up with each type of tool. With new tools, we look for new problems (or new ways of looking at old problems). When exposed to new problems, them we seek to equip ourselves with new tools.

Some open ended questions for fellow builders:

- Are you aware of when you are designing, building, or assembling?

- Has a new tool offered you a different perspective on an existing problem?

- Have you encountered a situation where you didn't have the tools you thought you needed? How did that change how you thought about the problem?

- Can you think of a situation where the tools used influenced your thinking of a problem? Was it to an overall benefit, or drawback?

Photo Credit Julie Molliver On Unsplash

This writing was last updated Oct 13, 2025. It is part of a larger series of reflections, and how they continue to shape my journey as a builder and educator. It is also an effort to bring humanity back into the online world. No AI was used in this piece.